District 20 is pleased to announce the 2025 winners for this year’s district 20 Voice of Democracy (VOD), Patriot’s Pen (PP), and Teacher of the Year (TA) competitions.

2025 Patriot’s Pen (PP) Winners

- Kedy Ren – Post 6012

- Lalani Tapaidor – Post 8397

- Saket Nadimpalli – Post 12041

2025 Voice of Democracy (VOD)

- Erin Martin – Post 2059

- Hailey Wilson – Post 7108

- Kiana Hampton – Post 837

2025 Teacher of the Year (TA) High School

- Amanda Aguiler – Post 4676 Grades 7–8

- Kevin Murphy – Post 2059 Grades K–6

- Sarah J. Olivera – Post 7108

- Details

- Written by: Johnathon Farrell

- Category: News

- Hits: 18

Fifty-two years ago, on January 27, 1973, the world witnessed a historic milestone in the long and painful chapter of the Vietnam War. The Paris Peace Accords—formally known as the Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam—were signed in Paris, France, marking the official end of direct United States military involvement in the conflict. For the millions of American veterans who served with courage and sacrifice, this agreement represented a hard-fought step toward bringing our troops home, securing the release of our prisoners of war, and upholding the principles of freedom and self-determination that so many fought to defend.

The accords came after more than four years of arduous negotiations, often conducted in secret. Leading the American delegation was National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, whose determined diplomacy played a central role. On the North Vietnamese side, Politburo member Lê Đức Thọ was the key negotiator. Their efforts earned both men the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize (though Thọ declined the award). The signing ceremony itself brought together representatives from the United States, the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam), the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam), and the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam.

Here are iconic images from that historic signing on January 27, 1973, capturing the solemn moment at the negotiating table and the handshake between Kissinger and Thọ:

The core provisions of the accords reflected difficult compromises made in pursuit of peace:

- An immediate cease-fire across Vietnam.

- The complete withdrawal of all U.S. troops and military personnel within 60 days.

- The release of American prisoners of war (POWs), with 591 Americans returning home between February and March 1973.

- Recognition of the sovereignty and right of the South Vietnamese people to self-determination.

- The continuation of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) at the 17th parallel as a provisional boundary, with the goal of eventual peaceful reunification.

- The establishment of an International Commission of Control and Supervision (composed of Canada, Hungary, Indonesia, and Poland) to monitor compliance.

These terms allowed North Vietnamese forces to remain in the South—a concession that proved controversial—but they also preserved the existence of the Republic of Vietnam government under President Nguyen Van Thieu and committed the United States to postwar reconstruction aid.

For American veterans, the accords carried profound meaning. They brought an honorable end to our nation's direct combat role, fulfilled the promise to bring every American home, and demonstrated the resilience of our service members who endured years of hardship in defense of freedom and anti-communist ideals. The release of POWs was especially poignant—a moment of joy and relief after years of uncertainty for families across the United States.

These images remind us of veterans and communities reflecting on the legacy of that day, honoring the sacrifices made and the hope for lasting peace:

Sadly, the peace proved fragile. Violations of the cease-fire occurred almost immediately, and full-scale fighting resumed within months. By 1975, North Vietnamese forces overran the South, leading to the fall of Saigon and the reunification of Vietnam under communist control. The accords did not deliver the lasting peace many hoped for, yet they stand as a testament to American determination to seek honorable resolutions and to the unwavering service of those who answered the call during one of our nation's most challenging conflicts.

To our Vietnam-era veterans of VFW Post 8555: Your valor, endurance, and patriotism remain an enduring source of pride. The Paris Peace Accords marked a chapter's close in a war that tested our nation, but your legacy of duty, honor, and love of country continues to inspire generations. We remember, we honor, and we thank you.

- Details

- Written by: Johnathon Farrell

- Category: News

- Hits: 66

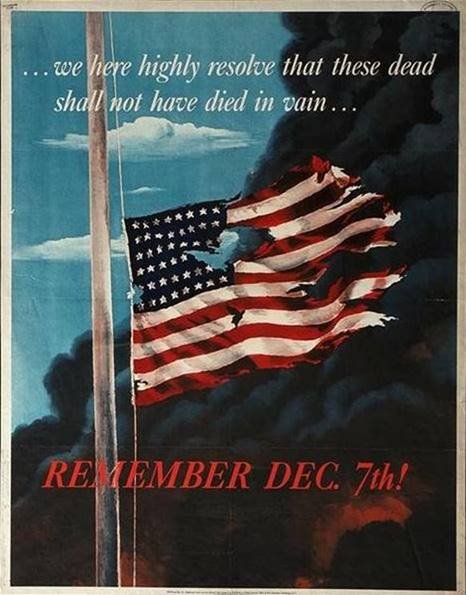

In the United States, December 7 is one of the most solemnly remembered dates in the nation’s history. On that day in 1941, Imperial Japanese forces launched a surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, drawing the United States into World War II and profoundly reshaping its role in the world.

The Attack on Pearl Harbor – December 7, 1941

At 7:55 a.m. Hawaiian time, the first wave of 353 Japanese aircraft—fighters, high-level bombers, dive bombers, and torpedo planes—struck the U.S. Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor and nearby airfields. A second wave arrived approximately one hour later.

In under two hours the attackers inflicted devastating losses:

- 2,403 Americans killed (2,335 military personnel and 68 civilians), including 1,177 sailors and Marines aboard the battleship USS Arizona

- Approximately 1,178–1,272 wounded (minor discrepancies exist depending on source and inclusion of lightly injured)

- 18 ships sunk, beached, or heavily damaged, including all eight battleships present

- 188 aircraft destroyed and 159 damaged on the ground

The three U.S. aircraft carriers of the Pacific Fleet—USS Enterprise, Lexington, and Saratoga—were at sea and escaped the assault unscathed, a fact that would prove critical in the months ahead.

“A Date Which Will Live in Infamy”

On December 8, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed a joint session of Congress. In a speech lasting just over six minutes, he declared December 7, 1941, “a date which will live in infamy.” Congress declared war on Japan that same day, with the Senate voting 82–0 and the House 388–1 (the sole dissenting vote cast by Rep. Jeannette Rankin of Montana). On December 11, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States, completing America’s entry into World War II on both the Pacific and European fronts.

National Pearl Harbor Remembrance Day

In 1994, Congress officially designated December 7 as National Pearl Harbor Remembrance Day (Public Law 103-308, signed August 23, 1994). Each year the president issues a proclamation urging Americans to observe the day with appropriate ceremonies and to honor all those who died or suffered because of the attack.

Standard observances include:

- U.S. flags flown at half-staff on federal buildings, military bases, naval vessels, and U.S. diplomatic posts abroad

- A moment of silence at 7:55 a.m. Hawaiian Standard Time (12:55 p.m. Eastern Standard Time)

- Wreath-laying ceremonies at the USS Arizona Memorial in Pearl Harbor and at memorials nationwide

The USS Arizona Memorial and Survivor Interments

The battleship USS Arizona suffered the greatest loss of life that morning. A Japanese armor-piercing bomb detonated her forward magazine, causing a catastrophic explosion that sank the ship in minutes and killed 1,177 of her crew—nearly half of all Americans lost that day. The sunken hull remains where she went down, serving as the final resting place for more than 900 sailors and Marines still entombed within.

Since 1982, the National Park Service and U.S. Navy have permitted surviving USS Arizona crew members to have their cremated remains interred inside the ship by Navy divers, reuniting them with their fallen shipmates. More than 40 survivors have chosen this honor. The last known USS Arizona crew member, Lou Conter, passed away on April 1, 2024, at age 102.

As of late 2025, fewer than ten known survivors of the Pearl Harbor attack remain alive, all over 100 years old.

A Fading but Enduring Memory

In the decades immediately following the war, December 7 was observed with a gravity comparable to Veterans Day. As the generation that experienced the attack has nearly passed, large-scale national remembrance has gradually become more localized—centered in Hawaii, at veterans’ organizations, and among military communities. For many younger Americans, the date is now most familiar through Roosevelt’s famous phrase rather than personal or family memory of the event itself.

Yet every December 7, flags are lowered, wreaths are placed, and the nation pauses to remember the morning that changed the course of the 20th century. In President Roosevelt’s enduring words, it remains a date which will live in infamy—and in the grateful memory of the United States.

- Details

- Written by: Johnathon Farrell

- Category: News

- Hits: 76

A Revolution Born in a Tavern

From Belleau Wood to Iwo Jima

Traditions That Bind 250 Years

The birthday celebration itself is the oldest military tradition in continuous practice. The ritual is codified in Marine Corps Order 5060.20:

- The Cake: A sheet cake for the unit, a smaller cake for the oldest and youngest Marines present. The first slice goes to the guest of honor (usually the oldest Marine), who passes the second slice to the youngest—symbolizing the transfer of experience.

- The Reading: Every command reads the 1775 resolution and Commandant General Lejeune’s 1921 birthday message, which reminds Marines they are “first to fight” and keepers of an unbroken legacy.

- The Ball: Dress blues, swords, and the Empty Table ceremony honoring missing comrades. The Marine Corps Birthday Ball is the only military event where enlisted and officers dance the same floor as equals for one night.

Beyond November 10, traditions run deep:

- The Eagle, Globe, and Anchor: Earned only after The Crucible, the 54-hour capstone of boot camp. Recruits are no longer “maggots”; they are Marines.

- The Blood Stripe: Red stripes on NCO and officer trousers commemorate the 1847 Battle of Chapultepec, where 90 percent of Marine officers fell storming Mexico City’s castle.

- Semper Fidelis: Shortened from Duke of Exeter’s motto, it became the official Marine motto in 1883. The Marine Band plays it as “Semper Fi” at every change of command.

250 Years Strong

- Details

- Written by: Johnathon Farrell

- Category: News

- Hits: 113

American Legion compiled List of Discounts and Venues

- Details

- Written by: Johnathon Farrell

- Category: News

- Hits: 132